Review: This Barbie is Thinking About Death

Greta Gerwig’s ‘Barbie’ allows the titular doll to step out of her box

The Yearning Rating: ✰✰✰✰

Romance: ✰

Sex: ✰

Storytelling: ✰✰✰½

Performance: ✰✰✰✰½

Yearning: ✰✰✰✰✰

9 out of 10 Barbie Doctors recommend liking our posts <3

Spoilers ahead!

Written by Ali Romig

This past weekend, I went to a Barbie Party. It tickled me to see all of the people there—gay, straight, lesbian, queer, non-binary, whoever—dressed up as different versions of Barbie, Ken, Allan, Midge (again, whoever!) depending on who they wanted to be that day. At some point during the fête, someone asked the group, “How did you play with your Barbies?” It may sound like an easy question—how many ways could there possibly be? But anyone who had Barbies as a kid knows the variety in game play is nearly endless.

The cold open of the box office smash, Barbie, does a bang-up job of illustrating just how disruptive the seemingly innocuous “Barbie doll” was when it was first introduced by Ruth Handler in 1959. Up until that point, the predominant doll for young girls was the baby doll, a toy that immediately forced children into the role of “mother.” Barbie, on the other hand, encouraged young girls, gays, femmes, and thems to imagine the doll as an extension of themselves or a test run of their imagined, super chic future. You’d get a Barbie, and yeah, the box might tell you the background of the doll you were playing with (President? Firefighter? Vet? Beach?), but for the most part you’d take the Barbie out of her box, toss the packaging, and make up your own story for her.

My particular go-to? I played with Barbies as if I were plotting an elaborate, sapphic soap opera. All my Barbies were having affairs with each other. I only had one Ken doll and his role was mostly to sit apart from the others—an easily forgettable husband away on “business”—while I smashed my Barbies’ silicone faces together. A game of lust and passion and illicit drama1.

As I think back on this childhood ritual—the discarding of the box, the creation of a brand new story—it almost feels like a small declaration of independence. Don’t tell us who Barbie is! Let us decide! Even still, playing with Barbie wasn’t all about liberation and creativity. No matter what story we gave her, she remained an idealized version of a woman. I don’t need to go into the unrealistic features of Barbie—her waist size, her bust size, the fact that her feet are literally made for heels—it’s all been cataloged countless times before. The fact is, Barbie was never meant to be attainable or relatable—or even really human. As Ruth, played by Rhea Perlman, says in the film, “Humans only have one ending. Ideas live forever.”

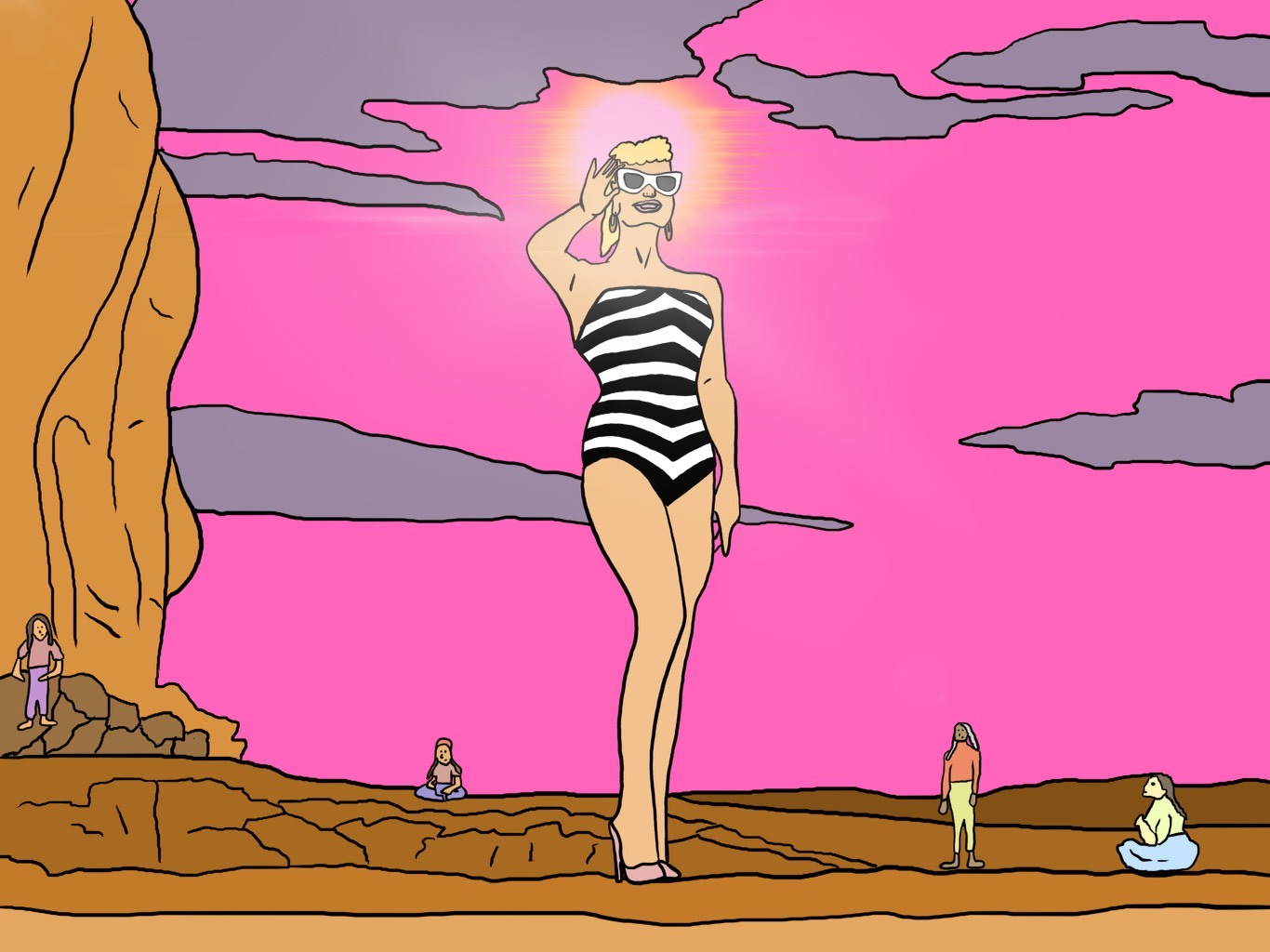

That thesis underlies much of this campy, aesthetic-fueled comedy that manages to take everyone’s favorite blonde bimbo and turn her into a femme Odysseus, traveling far from home on her own kind of Pepto Bismol hued hero’s journey.

Directed by Greta Gerwig, and written by Gerwig and her husband Noah Baumbach (The Marriage Story), Barbie aptly highlights the ways in which “ideas” can corrupt and confuse us, becoming dangerous for the very reason they’re attractive—they never die. Barbie Land is a world made up of ideas, of womanhood, of manhood, of who or what you can be. Never question any of it, and you’ll remain happy forever and ever, Amen. This is explained succinctly by one of my favorite lines in the movie: “You’re either brainwashed or you’re weird.”

In terms of plot, the film is better for its simplicity. Stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie) has the perfect life. She has tons of accomplished Barbie friends, a Dream House that’s all her own, and dance parties every night. But when she suddenly becomes plagued with thoughts of death and loneliness, she seeks answers in the Real World. Desperate for her attention, Ken (Ryan Gosling) tags along. When they return to Barbie Land, Barbie brings along two humans—a bickering mother-daughter duo (America Ferrera and Ariana Greenblatt, respectively)—and Ken brings his newly acquired knowledge of the patriarchy. Barbie Land experiences a Kenaissance overnight, with Barbie desperately seeking a way to right things, even as she isn’t sure what purpose she serves anymore.

The first half of this film stands out as incredibly strong. I loved being whisked away to Barbie’s world of stylized hyperfemininity, where cleverly placed details and astute in-jokes ran the show. Moments lampooning Barbie’s lore—from discontinued dolls, to groovy clothing sets, etc.—elicited marked reactions from the audience. There was a sense of shared experience as we all laughed, acknowledging that yes, we too had a “weird Barbie.” In fact, the inclusion of Weird Barbie (Kate McKinnon) was genius on many levels. Not only is it incredibly true to life, but it serves the added purpose of illustrating how idealized versions of womanhood won’t—nay, can’t—survive the real world. After all, what kid buys a Barbie with the intention of keeping it pristine? I personally believe we all eventually succumb to the impulse to “play too hard.”

I appreciated the feminist perspective of Barbie, but for me the more interesting interpretation is a queerer one. (And no, it has nothing to do with the fact that Barbie listens to the Indigo Girls multiple times throughout the film, a cheeky way of indicating her female utopia.) Underneath the bubblegum pink and baby blue aesthetics that misleadingly suggest a simple battle-of-the-sexes arc is a very clear message: gender is a thinly veiled construct. It’s an idea, maybe the most annoyingly indestructible of all. In Barbie Land, there are no “men” or “women” as most people understand them, there are simply “Barbies” and “Kens”2—genitalia-less hunks of plastic whose entire personalities are dictated to them by God, aka Mattel. The beauty of this loving satire is in watching our dolls discover that their boxes no longer fit, and that the roles they’ve been forced into don’t have to be permanent. Gender is drag, Gerwig seems to be saying, and it's as interchangeable as Ken and Allan’s clothing. We see both Barbie and Ken suffer at the hand of gender essentialism. Barbie in the Real World, and Ken in Barbie Land, where no one cares about where exactly he sleeps (certainly not in Barbie’s Dream House!). And eventually, we see them both move away from this rigidity, and towards something vaster, scarier, and so much more beautiful.

When she first heard she was cast in the film, trans actor Hari Nef almost had to turn down the role due to a scheduling conflict. As a last ditch effort, she wrote a letter to Greta Gerwig begging her to “fudge the schedule” so Nef could keep her role (and we are so glad she did—A+ fake barfer). She shared a bit of her letter on Twitter earlier this year, and it eloquently explains how Barbie’s version of womanhood can be both freeing and reductive, depending on your perspective. The nuance is in seeing Barbie’s femininity as an expression, rather than a necessity. Nef says, “Me and my other transgender girlfriends started calling ourselves ‘the dolls’ a couple of years ago, though the phrase stretches back into the language of our foremothers in the ballroom scene. The Dolls. Maybe it’s a bid to ratify our femininity, to smile and sneer at the standards we’re held to as women. It’s a joke, of course. But underneath the word ‘doll’ is the shape of a woman who is not quite a woman—recognizable as such, but still a fake. ‘Doll’ is fraught, glamorous; she is and she isn’t. We call ourselves ‘the dolls’ in the face of everything we know we are, never will be, hope to be.”

I know there are nuances to the making of Barbie, not least of which is that Mattel was heavily involved in the production. There is certainly something to be said about Robbie’s Barbie crying as she’s called a capitalist commodity, all while Mattel is no doubt making bank on merch (I hear that the Movie Barbies are going for fifty bucks a pop, and I’m sure sweatshirts bearing the adage “You are Kenough” will be everywhere soon). But taking this movie at face-value, it’s joyful and campy and made me laugh, and for that alone, I think it’s more than worth the watch. Not to mention, there was something special about sitting in a theater filled with people of all ages and backgrounds and luxuriating in this shared childhood experience—whether you’re laughing with it or at it. I think that’s pretty rare in today’s evermore-isolating world. And indulging in the reclamation of nostalgia can be pretty healing if you let it in.

I’ll admit—don’t hate me!—not all of the Ruth stuff landed 100% with me. The scene in which Ruth and Barbie speak against a white backdrop felt vaguely Harry Potter-esque. But I loved when Barbie told her, “I want to be the one who does the imagining, not the idea.” Who wouldn’t want to have this moment with their maker/mother/mastermind? A moment to assert your autonomy, and be met with acceptance. We’re born in our boxes, with expectations thrust upon us, either because of our perceived gender, or our families, or society. But just like my adulterous lesbian Barbies, we should all be allowed, if not encouraged, to step out and discover who we are and how we want to be—in our bodies, in the world—on our own terms.

Barbie is now in theaters, you can get tickets here (but really, haven’t you seen it already?)

Next week on The Yearning, Meg takes a walk through time with a review of HBO’s The Stroll.

It may be relevant to note that I started watching Desperate Housewives at age 8.

Also, Allan and Midge.

Love the use of fête in this review! So classy 💕

"The scene in which Ruth and Barbie speak against a white backdrop felt vaguely Harry Potter-esque." FRICK thank u for ruining this for me forever hahahahah