Review: Part of the Family

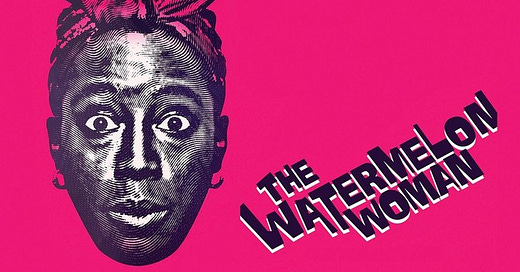

'The Watermelon Woman' is both romantic comedy and pivotal Black cultural text

The Yearning Rating: ✰✰✰✰ ½

Romance: ✰✰✰✰

Sex: ✰✰✰✰✰

Storytelling: ✰✰✰✰ ½

Performance: ✰✰✰ ½

Yearning: ✰✰✰✰✰

Happy Black History Month and (almost) Valentine's Day, Yearners. This felt like the right choice for this week <3

Written by Meg Steinfeld-Heim

I’m watching The Watermelon Woman and I can still remember the carpeted aisle and the feeling of a smooth, hard plastic VHS case in my hand. The confusion of its empty weight; a clunky plastic cavern, nothing inside of all that space. That is, until I got to the counter at Blockbuster and my Dad exchanged it for the real thing. Watching Cheryl and her best friend Tamara working at a small VHS rental shop in ‘90s Philly, the sense memory is as strong as ever.

Cheryl (played by writer and director Cheryl Dunye) is a mid-twenties Black lesbian filmmaker who is particularly interested in films from the 1930s and 1940s that feature Black actresses. In some of these films, Cheryl is shocked to discover that the Black actresses aren’t even listed in the credits. And this is an important historical reference, as this is very much true—many Black actors and actresses were systematically left out of the credits in early 20th century cinema. After watching a movie titled Plantation Memories in which a captivating Black actress playing a “mammy1” is credited only as “The Watermelon Woman”, Cheryl is indignant—why is there nothing to identify the real woman and actress behind the performance? Cheryl decides she’s going to try and figure out who this woman was and tell her story in a documentary. After showing a clip from Plantation Memories, she says fondly, “Girlfriend has it going on. Something in her face…something in the way she looks and moves is serious, is interesting.” And as a viewer, of course, you’re drawn into Cheryl’s devout admiration of her.

What are the different ways that a story can live inside of a movie? The Watermelon Woman’s premise has a really unique answer to this question. We’re watching a fictionalized story told by the Black lesbian filmmaker Cheryl Dunye, in which a young Black lesbian filmmaker lives in her queer community, dates, finds love, and also makes a documentary about a seemingly forgotten Black actress. There is history, fiction, culture, comedy and romance, all in 85 minutes. I hesitate to use the word mockumentary, even though I know it’s technically accurate, because while there is definitely a tongue-in-cheek humor to the project, no part of The Watermelon Woman feels overtly silly or satirical. (Maybe I just need to briefly drop out of the Christopher Guest School of Film.) The movie flows from piece to piece with title card transitions and expressive fonts that make you nostalgic for both Ken Burns and 90s sitcoms. You never feel the weight of all of these layers obstructing your understanding of the story though—Cheryl talks just as easily to us, the viewers of her documentary, as she does to friends or coworkers in her day to day life.

Both in her relationships and in her determined pursuit of information on the Watermelon Woman, Cheryl is earnest, passionate, and charming, and also—let’s not fight the romcom allegations—she is very, very cute. Her demeanor makes the entire movie irresistible. There is a sense that Cheryl is, at all times, vulnerable and potent—showing you exactly who she is. And because this character feels so close to who Cheryl Dunye (the real-life filmmaker) is, it’s a privilege to watch Cheryl inside The Watermelon Woman. When someone gives so much of themself to live inside a story, you can just feel it.

A path of information and sources unfurls in front of Cheryl, getting her closer to the heart of the Watermelon Woman’s story as a Black actress resisting the pigeonholes of racism in her chosen career. Cheryl’s mother recalls seeing the Watermelon Woman singing in clubs in Philadelphia and refers her to her friend Shirley. When interviewing Shirley and taking in all of her stone butch glory, Cheryl first uses the phrase that goes on to become a codeword throughout the film: “I think she’s part of the family,” she says to us, her viewers, and you can hear the conspiratorial smile in her voice. That warm queer camaraderie is so familiar; like a language we can all speak with each other no matter how old we are or where we came from. That’s heaven!!

When talking about the Watermelon Woman, Shirley gives us a real name for the first time—Fae Richards. She suggests that Fae may have been in a relationship with Martha Page, the white woman who directed Plantation Memories and several of the movies that Fae was cast in. A series of archival photos and grainy clips sets Fae opposite a masc Marlene-Dietrich type woman and suggests a definite intimacy between them.

And outside of the documentary project, in walks Cheryl’s love interest. Diana, a casually seductive white woman with big juicy lips, hits on her while checking out a movie at the rental store. Romcom alert—or so it may seem at first? After repeated attempts by Tamara—who is blissfully obsessed with her Black girlfriend Stacey—to set a disinterested Cheryl up with various Black queer women, the two begin to date. Their relationship is hot (there is an impressively explicit sex scene for 1996 that caused enough conservative outrage to make it to the House floor). But Tamara takes serious issue with Diana, saying she “wants to be Black” and icing Cheryl out when Diana’s around. Stacey doesn’t like Diana either, and the wedge between these Black lesbians is driven deeper.

In examining the relationships between Tamara, Cheryl, Stacey and Diana, The Watermelon Woman is not asking easy questions or providing any simple answers. Tamara calls on Cheryl’s continued interest in white girls as a suggestion of her failing Blackness. Cheryl begins to see past the initial attraction to Diana to understand that they may not be that well matched; after all, Tamara has some points about Diana “volunteering with poor Black youths”. Diana lets slip racial comments that are fetishy. But does Cheryl need to embody her Black lesbianism according to Tamara and Stacey’s standards? Do I have to desire who I am?

Outside of her spiraling personal life, the Watermelon Woman research continues for Cheryl. In the most Guestian moment of the whole movie, a self-important white woman academic offers a glowing, positive perspective of the “mammy” stereotype and rejects its cultural baggage. The reality of the missing Black historical archive is depicted by a floundering unhelpful librarian. Then—a revelation at the Center for Lesbian Information and Technology (CLIT, lol) confirms that Fae was queer and was in a long term relationship with a Black woman named June Walker. Cheryl and June speak on the phone, and June sheds light on who Fae was as an actual human being: not just an actress, or someone who played “mammy” types, or who was maybe the pet of a privileged white lesbian director (as Cheryl speculated).

June is derisive and upset at the mention of Martha Page—"Don't you know she should have nothing to do with how people should remember Fae?” As June recounts a lot of tenderness in their twenty years as a couple, the reality of their relationship takes up space in Cheryl’s growing picture of Fae Richards. Also noteworthy is the way that June talks about Martha and how it echoes Tamara’s resentment of Diana. The Watermelon Woman explores power dynamics between interracial couples in this way. Diana gains credibility from her proximity to Cheryl and her Blackness. Similarly, was Martha Page taking advantage of Fae via the inequal power dynamic between them—a successful, white woman director and a Black actress striving for mere name recognition?

This forces further speculation for Cheryl—her words directed at June, she says, “I know she meant the world to you. But she also meant the world to me. And those worlds are different. But the moments she shared with you, the life she had with Martha on and off the screen, those are precious moments…and nobody can change that. But what she means to me…hope, inspiration, possibility…it means history!” I think the value of knowing Fae Richards in her entirety is in the spirit of everything The Watermelon Woman is trying to say.

While Cheryl is trying to land on her documentary project subject, she prefaces the decision by saying: “I know it has to be about Black women, because our stories have never been told.” Both Cheryls—the character and the creator—manage to do that with this film. A title card at the end of the movie reads, Sometimes you have to create your own story. The Watermelon Woman is fiction. I see it also as a kind of handbook—move forward, know these women, tell these stories. Even though it’s a fictional story, Dunye is making one thing plain: this is how Black history should be excavated and cared for, protected and adored.

Have you watched The Watermelon Woman?

Traitor Behavior

Season 3, Episode 7:

Another day, another episode where Carolyn, Rob, and Danielle all say to each other in the Tower, “This week we’re starting over. I promise.” And then continue planning to backstab each other.

A truly excellent and simple challenge this week had pairs of competitors holding hands inside of a see-through box while Alan’s minions dumped all matters of creepy crawlies inside. And on their heads.

Tom Sandoval is, for once, right about Rob as his primary Traitor suspect, and tells everybody who will listen. But his complete and utter lack of credibility seems to be helping Rob, until…the votes come out, and Rob is banished (with the help of his fellow Traitors. Naturally!). It’s a Traitor eat Traitor world out there.

Gabby Windey is vulnerable to be murdered and if she is I will boycott!! When will I get my Gabby Traitor arc :/

Next episode of The Traitors Season 3 comes out tonight at 9p ET!

This is a racist historical stereotype of a Black woman, usually enslaved, who did domestic work like raising children, cooking, and cleaning. She was usually portrayed as having dark-skin, a motherly, caring personality and a simplistic nature.