Guest Post: 365 ‘Party Girl’ (Bumpin’ That)

Parker Posey’s leading lady debut, best paired with a falafel & hot sauce, a side of baba ganoush, a seltzer, and a nice, powerful mind-altering substance

The Yearning Rating: ✰✰✰✰

Romance: ✰✰✰✰

Sex: ✰✰✰

Storytelling: ✰✰✰✰

Performance: ✰✰✰✰✰

Yearning: ✰✰✰✰

Today’s guest post is written by known Lincoln-expert Abby Conners, back for another go-round for The Yearning. We are so lucky <3

Written by Abby Conners

If you’ve been within ten feet of any screen this spring, you know that the internet has gone buck-wild for Parker Posey. She charmed the masses with her deliciously satirical role as Victoria Ratliff, the matriarch of the well-to-do, but poorly behaved Ratliff family in the third season of Mike White’s The White Lotus (streaming now on HBO Max). Her character’s dialogue has reached near ubiquity with few lines from television as parroted as “Piper no!” in recent history. My first exposure to Parker Posey was in the 2001 anti-capitalist manifesto and my personal favorite Posey movie, Josie and the Pussycats. Posey portrayed the former-weird-girl-turned-evil-CEO Fiona colluding with closeted albino, Wyatt (played by Alan Cumming), to use subliminal messaging in pop music to sell stuff to teens. By the time I’d discovered her, Parker Posey had already been firmly established as a capital-G-capital-I Gay Icon and indie darling; a title she’s held throughout her more than thirty-year film and television career. It’s been my delight in the twenty-four years since Josie and the Pussycats to immerse myself in Posey’s oeuvre: Coneheads (1993), Dazed and Confused (1993), Clockwatchers (1997), Best in Show (2000), Adam & Steve (2005), among others.

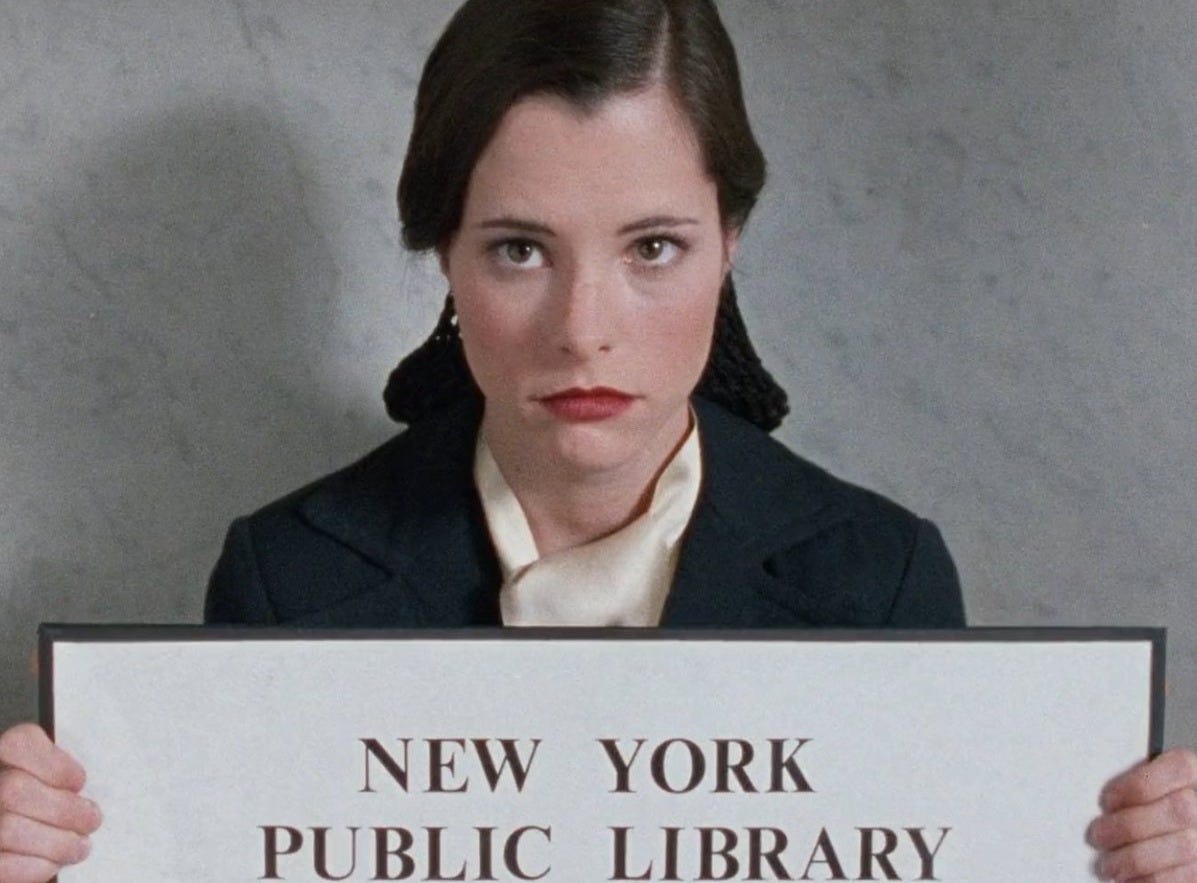

The Yearning has generously granted me the opportunity to proselytize about Posey’s first leading role, which launched her into the queer zeitgeist for good: Party Girl (1995). Directed by Daisy von Scherler Mayer1, this zany, sometimes unstructured, ninety-four minute film about a club kid-turned-aspiring-librarian roots itself smack-dab in the middle of the queer underground in 1990s New York City.

Party Girl opens on Lady Bunny (a contemporary of RuPaul) in full drag, feverishly preparing for her grand entrance into the illegal, underground rave that Mary is throwing. Busted while charging cover at the door to pay her rent, Mary is thrown in jail and bailed out by her stern godmother, Judy (played by Daisy von Scherler Mayer’s mother Sasha), on one condition: she has to join Judy in working for the New York Public Library. When Mary is not begrudgingly at work, she strikes up a casual romance with a young Lebanese man, Mustafa, who runs her neighborhood falafel stand. At the same time, she begins an unexpected love affair with library science, growing a newfound appreciation for both the on-the-job and nightlife uses for the Dewey Decimal System.

A daughter of a “mother with no common sense”, Mary’s sisyphean rock does occasionally roll back down the proverbial hill. Mary impulsively invites Mustafa over to the library one night and they take good advantage of the space and alone time and neglect to properly close the windows before an unanticipated rainstorm. Her forgetfulness is not without consequence, she’s let go from the library and forced to hawk her vintage Gaultier frocks at consignment shops for cheap. She manages to bungle it with Mustafa as well, stoking his jealousy with her bouncer ex-boyfriend, Nigel, played, both randomly and to my delight, by Liev Schrieber. Fear not, Mary is like a weeble-wobble and she always gets back up. Through sticktoitiveness, creativity, and, naturally, the Dewey Decimal System she manages to get the guy, get the job, and find the courage to break expectations.

Party Girl is replete with jumping points for compelling cinematic discourse. The fashion alone in this film deserves 10,000 words, an endeavor that Vogue took on in 2020 if you’re keen for a deeper dive. Posey’s looks in the film are eccentric, vintage, and lean heavily on nylon tights. They conjure all the good things about Man Repeller in 2015 minus Leandra Medine’s casual racism and pro-Zionism. The soundtrack is also integral to the film, house music ever presently bringing to life a multi-cultural, immigrant-driven, and queer New York as the backdrop to this story. For more on this: Pitchfork! I’m available to write!

I’d be remiss to not shine a light on these important stylistic elements of the film, but my proselytizing to you is predicated, in part, on making the case for why Party Girl is canonically queer and beyond worth a watch. You’ve come to The Yearning because you’re queer, a voracious consumer of queer media, or you are, at least, a little bit curious about queer media. Or you follow me, Ali, or Meg on Instagram and are a good friend (or parasocial enemy). In considering queer media for this conversation, let’s go with the definition that queer media is any media that centers (1) queer people (open to interpretation) doing (2) queer things (broadly). Meg – in her critique of TikTok Tinx’s “not queer” queer book, Hotter in the Hamptons – argued that the power of queer storytelling lies not only in the content itself, but also in who tells queer stories and how they are discussed in the public domain. For The Yearning, I’m thrilled to add my perspective to this conversation that Meg started about queer media, storytelling, and allyship.

In Party Girl, the central romance is straight, but this does not disqualify it from being firmly within the queer cannon. Von Scherler Mayer puts the NYC drag scene and club scene front and center in this film. Famous queens Natasha Twist and Lady Bunny make notable cameos and queer people of all orientations mingle freely and joyously in over-the-top club scenes. Party Girl’s queerness isn’t a gimmick, plot device, or a caricature, but a living, breathing setting for this story to take place. Neither Von Scherler Mayer nor Posey are out as queer themselves, but they both engage with the queerness in this film with honesty, care, and necessary attention-to-detail. Party Girl functions to elevate the queer community, creating visibility and representation for the diversity of people of which it is made up. Released in 1995, Party Girl arrived at the heels of the AIDS epidemic, but manages to show the levity and vitality of a remarkably resilient community and its dogged allies. This movie is campy, zany, out-of-pocket, and, ultimately, fun. Party Girl makes the case that non-queer people can effectively participate in and tell queer stories if they do so in meaningful partnership with actual, real life queer people. And if they give credit where credit is due. And if they genuinely care for and about queer people in their real lives. Allyship—like true, unwavering, willing-to-be-unpopular allyship—is the secret sauce for compelling queer stories told by cis and straight people.

Allyship is more than acceptance, more than merely being okay with the fact that queer people exist and do queer things. True allyship uses craft and care to amplify queer voices, center them in their own stories, and uses its privilege to make safely existing a little bit easier. There are a lot of ways that this is done well: hiring queer creators and artists and paying them well, using platforms and resources to shed light on issues affecting all corners of the community, or advocating for political platforms that support the rights and freedoms of queer people. In the spirit of creatives practicing what they preach: in addition to her acting and directing career, Sasha Von Scherler Mayer became a licensed social worker in the 1980s and served the gay community in New York through the AIDS crisis for more than a decade.

My undergraduate liberal arts degree requires that I take a moment to articulate a thematic parallel between Mary’s journey to adulthood and the queer experience. In all seriousness, it’s refreshing to see a queer movie without (1) a tragic death or (2) someone having to come out as gay. Posey spares us this, as Mary effectively ends the movie with her own coming out, defying expectations and veering away from her assumed life path. She announces to an audience of friends and family that, instead of the path they had visualized for her, she would instead follow her heart, and pursue a Master’s degree in Library Science.

As someone who has come out, and continues to come out on a daily basis, I felt a glimmer of kindred solidarity with Mary’s position. I’ll spare you too much after-school-special cheesiness, but part of the challenge of coming out is dealing with the fear of not being accepted for who you are. The other sneakier part, navigating beyond outward claims of acceptance and coolness, is the fear of surprising people and doing something they didn’t expect you to do. Or, I might just be revealing myself as a middle-child, Midwestern, people pleaser. You decide! So, fine, Mary doesn’t come out as a lesbian, bi-curious, or pan at the end of the film. But, the character does model what it looks like to defy convention.

Every queer person you know (very likely yourself if we’ve got the demographic of The Yearning’s readership right) has had a pivotal life moment where they had to sit down, consider themselves, the world, and if and how they fit into it. Part of the unspoken privilege of cisness and straightness is the peace of not having to explicitly question your own gender or sexuality, necessarily. The world is made for cis-straight people and social conventions have evolved to accommodate them. I find myself glad for and grateful to cis-straight people who are willing to engage in questioning, challenging, and dismantling social convention, even if it does not directly affect their personal life in the short term. That’s allyship—to share in the struggle to normalize and validate (and maybe even glamorize, ok?!) alternative, seemingly unconventional, or “subversive” ways of being.

Certain figures do this so publicly and consistently in their lives and in their work that they get elevated to the holy cadre of Gay Icon. In my not-so-academic opinion, traditional gay icons status is established through demonstrated alignment to some, or all, of the following key criteria:

Queer fashion or non-traditional aesthetics;

Queer sensibility (related to aesthetic but I’m referring more to energy than visual look), a campiness, palpable other-ness, and/or a willingness to subvert - even subtly - social conventions. This can be done through public persona or artistic expression through music, choice of film or television roles, vibe;

Gender identity or sexuality, and finally

Superior allyship, for those who both do and don’t identify as queer in some way.

Posey, despite being relatively tight-lipped about her private life, tends to hit the mark on the above. Her commitment to independent filmmaking distinguishes her from peers in her industry. Time Magazine dubbed her the “queen of the indies” in 1997. She’s maintained a commitment to working with small and independent filmmakers, despite lack of financial windfall, navigating the risk of diminishing indie opportunities or carving out a niche from which she could not escape into the mainstream. To our great fortune, Posey has clearly managed to toe that line and keep herself working, if the aforementioned White Lotus craze is any indication. I have to hope that we are in the midst of a spiritual Posennaissance, one that champions underfunded and up-and-coming artists. Unwavering and material support for queer film, television, and writing is needed more now than ever to counteract nefarious forces and populist fear-mongering. We’ll all wait impatiently to see how the sociopolitical climate and market forces evolve in coming months and years. But for now, as Mary put it so clearly, “I would like a nice, powerful, mind-altering substance. Preferably one that will make my unborn children grow gills.”

Party Girl is available for streaming on Peacock.

Von Scherler Mayer also has directing credits for episodes of Showtime’s Yellowjackets if you were in search of further commitment to queer media.