Essay: A Brand New Bombshell Enters the Peaceful Japanese Airbnb

How Love Island USA and The Boyfriend spin the same formula in opposite directions

Love Island Yearnometer: ✰✰✰

The Boyfriend Yearnometer: ✰✰✰✰✰✰✰

Validate my feelings about reality TV by liking this post :)

Some spoilers! Not many!

Written by Meg Steinfeld-Heim

Ahh…summer. Not exactly the golden season of television. Everyone knows that the summer is when you have the most distance from your twisted network of streaming service access — between vacations, cocktails in the backyard, and remembering what life is like without Seasonal Affective Disorder, there’s just so little time to bother your family for passwords or lie to Netflix about your location.

But what does feel right for a summertime watch? For me lately, it’s been sunny, bikini-clad reality TV, which is juicy and vapidly joyful, like a pleasant lobotomy. And so, I found myself for the first time watching Love Island. In the past, I’d gotten through maybe 32 minutes of an episode before I was bored as hell. It didn’t catch. But this summer, something clicked for me, and I became ridiculously invested in the silly, artificial stakes of recouplings, “closing things off”, and being “pulled for chats” in Love Island USA Season 6.

If you’re not familiar with the Peacock show, here is a very quick primer: about 10 “Islanders” (5 men and 5 women) are put in a villa. The objective of the show is to stay coupled up–and eventually, to be voted [insert host country here]’s Favorite Couple and win $100,000. You can become ‘Vulnerable’ to being ‘dumped’ from the villa if the person you’re coupled up with leaves you for someone else. Periodically, ‘Bombshells’ (unknown hot people) are added to the villa to upset the man/woman balance and force a dumping.

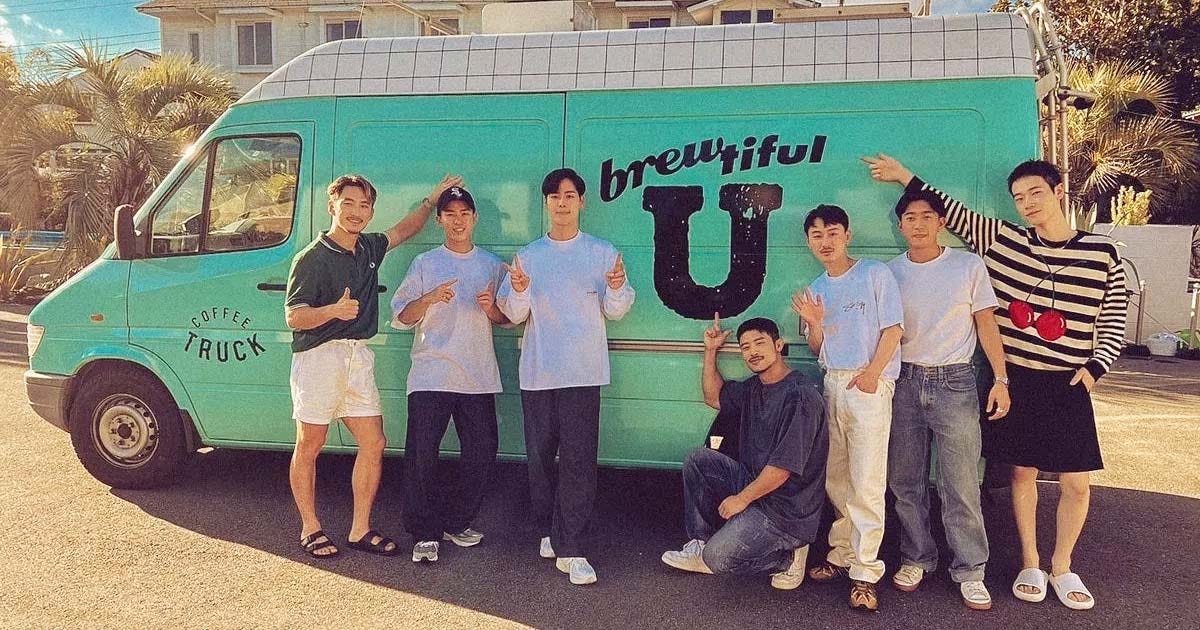

When the dust settled around the Love Island USA S6 finale, I was looking for something new. This is around the time that friend of The Yearning Jake Murphy asked if I had watched The Boyfriend yet. The Boyfriend is a new Japanese dating show on Netflix. It has essentially the same structure as Love Island, except it's queer – following 9 men from Japan and Korea, living together under the same roof and trying to find love. Instead of vying for a cash prize, these men are running a small coffee truck (🥹) and thoughtfully learning to cohabitate through budgeting and cooking together. And instead of one Love Island goofy host doing a constant Alan Cumming impression, The Boyfriend regularly features a lively, quirky panel of 5 queer Japanese commentators. They are tucked away in some studio to encourage, fawn over, and tanalyze our contestants.

Regardless of their fluff content, watching these two shows back to back has really become a study of tone and cultural context for me. In this essay I will…

I’ve been mulling this over: Love Island is packaged as very sexual and scandalous television. The conventionally beautiful contestants, the near endless amounts of swimwear, and the challenges designed to force bodies together by any gravitational means possible all contribute to this. But to me, its core essence is relatively chaste. The bed situation on Love Island was what first made me think about this: Choosing to sleep in the same bed as a partner indicates a feeling of emotional safety, intimacy, and maybe even commitment – all of that takes effort to cultivate. But Love Island cuts straight to the chase by forcing brand new couples to sleep in the same bed together from Day 1 – or else, you’re sleeping outside with the Fijian mosquitos.

It feels like this kind of forced intimacy between contestants actually tends to make them back off a bit from the jump. In modern American dating culture, sharing a bed can be so much more intimate than [just] having sex. On Love Island, you often see these awkwardly constructed “walls” of pillows between couples who just talked for the first time six hours ago. When Islanders have significant relationship decisions taken away from them, they have to resort to more middle-schoolian tactics to protect themselves. This is part of the show design that feels so distinctly juvenile to me. Cooties!!

And The Boyfriend literally talks about this. When two of the men, Kazuto and Alan, get the opportunity to go on an overnight date, those left behind (both with crushes on Kazuto) get into a conversation about what size bed(s) the overnighters might be sleeping in. “Hopefully it's a twin bed…I hope it’s a twin,” jokes Ryota, the 28 year old barista and model who has captured my heart. And the energetic panel of Japanese commentators, always watching over our sweet men, immediately weighed in: “If they’re in the same room, where they’re sleeping really matters…it opens the door for intimacy.”

Unlike Love Island, the contestants on The Boyfriend each have their own private sleeping quarters outfitted with twin beds. Even when the two arrive for their sleepover date, the hotel room has two twin beds. They’re very close together. And easily pushed together. But the contestants would have to make that choice, consciously, together. Similarly, to go on dates, the men have to openly share (by raising their hand, or writing a signed note) who they’d like to spend time with. It’s clear that The Boyfriend is designed to initiate intimacy differently–namely, by encouraging direct communication in spite of fear.

Love Island also utilizes choice–but theirs feels less equitable. Recouplings can happen at virtually any time. And these are not normal relationship check-ins or breakups; it almost seems against the ethos of the show to have an open and honest conversation with someone about how your feelings have changed. Oftentimes, Islanders learn of their newly Vulnerable status AT the recoupling, as they watch their person choose someone else and sheepishly avoid eye contact with them.

It is hard and scary to tell someone that you’re interested in them. Being direct about your romantic or sexual interest is brave; it steps right up to the plate of vulnerability and takes the best swing it can. It’s also, typically, damn near impossible to form a connection with someone if at least one of you doesn’t tell the other how you feel.

That feeling of ohmygodIhaveacrushonyou reminds me of the last days of 7th and 8th grade. My classmates and I would all be out of class for a pre-summer Field Day and romance was quietly unfolding left and right–after all, it was the last possible moment to become boyfriend/girlfriend before the damning isolation of summer. Bear with my dumb metaphor–sometimes, you should be on the brink, heightening the stakes. Be honest about your crush. Push yourself and ask for the partner you want. This is a central tenant that Love Island and The Boyfriend both rally around. Whether or not the connections made as a result are genuine or long lasting, the consensus is this: tell them!!

I am not Japanese and don’t feel comfortable weighing in on specific mechanisms of The Boyfriend as culturally “normal” or not, so I will just say this: to me, The Boyfriend feels revolutionary, as it is a neutral, empathetic space for these queer men to explore their sexual and romantic connections. Queerness is not criminalized in Japan, but is still highly stigmatized. It is not uncommon for modern Japanese parents to struggle accepting or supporting their queer children. LGBTQ+ marriage is not legal.

Aside from that, Japanese culture emphasizes harmony over individual aspirations, making people particularly sensitive to the thoughts and feelings of others. In a society as community-focused as Japan, shame comes easily when one feels they’ve failed to live up to the obligations or other’s standards of grace. This came through for me particularly when one contestant, Shun, breaks things off with Dai, citing many “concerns” he had over their short relationship–like the pictures Dai took of his own body, or his general exuberance on a date–that all felt more like a projection of Shun’s discomfort with Dai living an expressive, joyful queer life.

Love Island feels refreshingly shame-free. This is not to say it doesn’t feed on insecurities–it is most certainly a nightmare for anxiously attached people. But, petty beef aside, the Islanders are profoundly encouraging and kind to each other. Of course, there is heterosexual privilege at play here. You can expect the Barbies and Kens to feel pretty confident running around the Dreamhouse that was designed specifically for them. But, in a world where nearly every AFAB person I’ve ever met has deep-rooted insecurities about their bodies, Love Island and its contestants helm an unending hype machine. They are all fast friends, cheering each other on at challenges and spending all day worshiping how hot they all look in every outfit. It’s honestly pretty gay! (Also, I am holding space for a LI edit that may intentionally obscure the truth here).

The increasing depth of emotion in The Boyfriend confessionals demonstrates the emotional safety that was fostered there. You innately sense how much harder it is for these men to find their footing amongst their desires, their fears, and the culture they live by. By contrast, the heightened emotionality in Love Island confessionals comes more often from Islanders being pushed to the brink by manufactured rejection, dishonesty, and breaches of trust. (Poor Kaylor.)

But, I find Love Island builds a particularly beautiful intimacy between the friends found there at the villa. Contestants are not allowed to have their personal phones (they have these weird ones from production that only get texts that announce challenges or dates) and they have no contact with the outside world. There’s no TV, and a lot of downtime. So Islanders just…talk. All day! Particularly for the straight men on the show, I was impressed by their willingness to open up and confide in each other as the show progressed. You can just tell it is cathartic for them to be able to share so freely.

The Boyfriend is quiet, gentle, and tentative in every way that Love Island is zany, goofy and joyful. I love both shows, for different reasons, and I find it so interesting that one very simple reality TV show format could produce two such unique stories. I could talk about this for hours, and I would love to hear from you in the comments or over email if you have thoughts of your own.